![]()

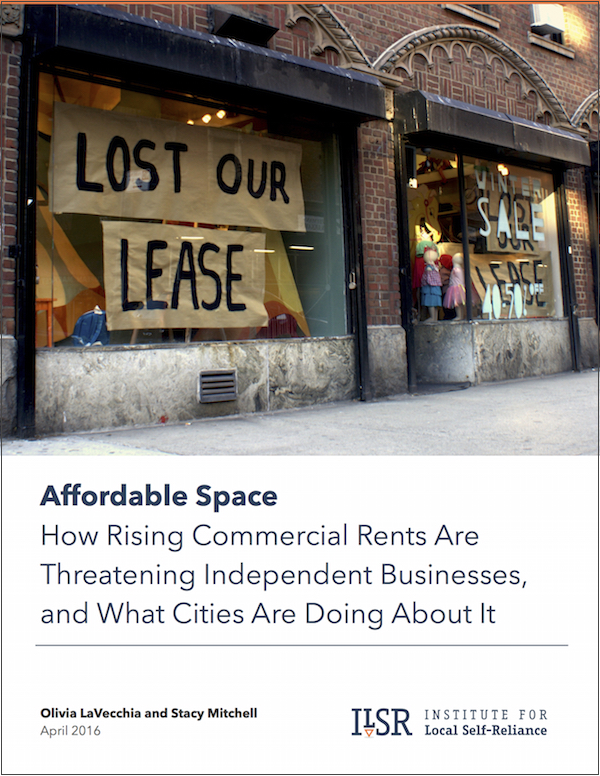

ILSR’s new report examines how high rents are shuttering businesses and stunting entrepreneurship, and explores 6 strategies that cities are using to create an affordable built environment where local businesses can thrive.

In cities as diverse as Nashville and Milwaukee, Charleston and Portland, Maine, retail rents have shot up by double-digit percentages over the last year alone. As the cost of space rises, urban neighborhoods that have long provided the kind of dense and varied environment in which entrepreneurs thrive are becoming increasingly inhospitable to them. Local businesses that serve the everyday needs of their communities are being forced out and replaced by national chains that can negotiate better rents or afford to subsidize a high-visibility location.

In cities as diverse as Nashville and Milwaukee, Charleston and Portland, Maine, retail rents have shot up by double-digit percentages over the last year alone. As the cost of space rises, urban neighborhoods that have long provided the kind of dense and varied environment in which entrepreneurs thrive are becoming increasingly inhospitable to them. Local businesses that serve the everyday needs of their communities are being forced out and replaced by national chains that can negotiate better rents or afford to subsidize a high-visibility location.

This new report from ILSR offers elected officials insights on what’s causing commercial rents to skyrocket, and explores six broad policy solutions, with practical examples, that cities can use to keep commercial space appropriate, accessible, and affordable for independent businesses.

The report finds that the sharp rise in rents is happening across a range of communities, with some of the most intense pressure falling on businesses in lower income neighborhoods. And the trend isn’t limited to retailers. The price of industrial space is rising rapidly too, jeopardizing a budding renaissance in urban manufacturing.

There’s a public interest in the commercial side of the built environment, the report concludes, and smart city policy has an important role to play in creating an urban landscape in which locally owned businesses can thrive.

Read: ONE-PAGE FACTSHEET | Press release | Full Report | MAPPING RISING RENTS

Introduction

For 22 years, Lisa Monson ran her business out of a building she rented in Salt Lake City’s 15th and 15th business district. The 2,800-square-foot space was a good size for her hair salon, and she liked being in a neighborhood of locally owned businesses.

Like many business owners, though, the more Monson continued to invest in her business, the more wary she became of losing her space. Her landlord wouldn’t offer her a long-term lease, and every three years, she faced a tough renegotiation. Meanwhile, national chains had started moving into the neighborhood, including a Starbucks and an Einstein’s Bagels that bought out a local bagel shop.

“It kept me in a place where I was completely at risk of being thrown out,” Monson explains. “I knew that if he got an offer for a lot more money, I wouldn’t be able to match it.”

The cost of commercial space is spiking upward around the country, driven both by run-away real estate speculation and the growing popularity of urbanism. As a new generation discovers the appeal of walkable and mixed-use neighborhoods,[1] demand for small commercial spaces in those neighborhoods is far outpacing supply, and rents are rising to match. Locally owned enterprises, which thrive in these areas, are increasingly threatened with displacement from the neighborhoods that they’ve made vibrant, and getting replaced by national chains that can negotiate better rents or afford to subsidize a high-visibility location. As high rents shutter longtime businesses, they also create an ever-higher barrier to entry for new entrepreneurs, stunting opportunity and leading to a scarcity of start-ups in cities once known for their business dynamism.

“The rents have come to be the most critical issue in the survival of locally owned businesses,” says Betsy Burton, president of the American Booksellers Association and a founder of the independent business advocacy group Local First Utah.

When once-thriving blocks become colonized by generic national brands, local business owners lose. But so do cities and the people who live in them. The businesses on the front lines of rising rents are the grocers and hardware stores, the neighborhood-serving businesses selling everyday goods with little padding on their margins. When these businesses get displaced, residents lose the ability to walk to the store for their shopping, to bump into neighbors, and to chat with the business owners, who often attend to a variety of community needs that go well beyond making sales.

Cities also stand to lose, because the strength of the independent business sector is closely tied to other policy aims. At a time when more than 30 major U.S. cities and counties have committed to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent or higher,[2] having local food markets, pharmacies, and other stores in neighborhoods has been shown to sharply reduce the amount of driving households do, and even to spur more people to commute to work by public transit.[3] Locally owned businesses also sustain much of the social fabric of neighborhoods, and recent research has found a strong relationship between their prevalence and community well-being, including higher income growth and lower poverty rates, as well as increased levels of civic engagement.[4] And for cities looking to increase jobs, fostering a built environment that’s small in scale and hospitable to local enterprises has been shown to support stronger levels of positive economic, social, and cultural activity across metrics from number of jobs per square foot to diversity of residents.[5]

The displacement of local businesses isn’t just an issue in trendy, affluent neighborhoods. Among New York City’s boroughs, the Bronx has seen the biggest jump in court-ordered evictions of small businesses,[6] and over the last year it also experienced the largest percentage increase in the number of chains.[7] Among these newly arriving chains is a Boston Market, slated to open on a busy corner previously occupied by Zaro’s Bakery, a beloved business founded by a Polish family in 1927 and given just a few weeks notice that its lease would not be renewed.[8] Across the Harlem River, in Washington Heights, numerous longstanding businesses have recently been evicted or handed hefty rent increases. One is the nearly 40-year-old Liberato Foods, a Dominican grocery store with two-dozen employees, which is reportedly facing a tripling of its rent.[9]

“I think affordability is a very high issue if not the highest issue that businesses face,” says Vicki Weiner, deputy director of the Pratt Center for Community Development, of local businesses in New York City. “What they make compared with what they have to pay in rent seems to be out of scale in every neighborhood, no matter what the market conditions are.”

Some cities and community leaders are beginning to grapple with the ways that public policy can offer solutions. They are coming up with innovative ideas, from tax abatements for new developments that set aside space for local retail to low-interest loan programs that help local businesses buy their buildings, all with the aim of creating and maintaining a built environment that’s affordable, appropriate, and accessible for locally owned businesses.

“We know that small businesses, particularly those that are neighborhood-based, are important contributors to the identity of Seattle, and the diversity and what makes it attractive to be here,” explains Ken Takahashi, who works in the Office of Economic Development in Seattle, of the perspective of one city. “So we don’t want to just let the market do what the market does, and we want to see if there are ways that we can intervene.”

PART 1: Understanding the Problem

“We’ve been priced out of a ZIP code that we’ve been in for the past 18 years,” wrote a local retailer in Austin in the comments of ILSR’s 2016 survey of independent businesses. “I don’t mean rents slowly creeping up; I mean we would be paying more than double.”

This business owner isn’t an outlier. In that survey, which was distributed to local businesses across North America, 59 percent of retailers reported being worried about the increasing cost of rent, and one in four described it as a top challenge.[10]

“I get calls every week,” says Rebecca Melançon, the executive director of the Austin Independent Business Alliance. “Our members are not seeing a 10, 15, 20 percent rise. Their rents are doubling, tripling, and quadrupling, and the economy is good, but they’re not bringing in four times their revenue. It’s basically forcing them out.”

Some locally owned businesses, like those with multiple locations or a higher-end product, can handle those increases. “It’s the older, smaller businesses that really built the city in a lot of ways that I see hurting,” Melançon says. It’s also impacting who can start a business. “Austin’s extremely entrepreneurial, but if you don’t have deep pockets, the threshold for entry has gone way up,” continues Melançon. “There isn’t anyone out there it’s not affecting.”

The average annual rent for a 2,000-square-foot store in the U.S. increased 2 percent in 2015, according to the real estate statistics firm Reis, Inc. Start drilling into cities and towns, and the numbers climb faster. In Charleston, for instance, citywide retail rents skyrocketed 26 percent between Feb. 2015 and Feb. 2016;[11] in Cleveland that figure was 12 percent,[12] and in Nashville, 20 percent.[13] Even in smaller communities, like Grand Rapids, Mich., the retail rents are “unprecedented.”[14]

Look at the rents for the kinds of walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods that have traditionally provided the best environment for locally owned businesses, and the numbers jump again. In Louisville, Ky., for instance, the lease rate for big-box retail space was $7.28-per-square-foot at the end of 2015. For “small shop” space, it was $16.68-per-square-foot, a 129 percent premium.[15] A 2012 study from the Brookings Institution found that Washington, D.C., neighborhoods that scored well on an index of walkability and urban design, called the State of Place Index, also had higher real estate values. “A one point increase in a neighborhood’s State of Place was related to increases of… $0.35/sq. ft. in retail rents, [and] four percent in retail revenues,” the report found. “Clusters of neighborhoods with an above average State of Place Index commanded nearly… 47 percent more in retail rents… than a neighborhood with an above average State of Place Index that ‘stood alone.’”[16]

Within particular business districts, often the ones that local businesses have made vibrant and valuable through their own investment and labor, the increases in rent are the sharpest of all. In Philadelphia’s downtown district, Center City, rents for prime retail space increased 87.5 percent over seven years, including 15 percent in 2015 alone. Along some streets, increases were as high as 214 percent over the last decade. “Some local merchants have been pushed off of Walnut [St.] as international and national brands move in,” notes a report from the commercial real estate firm CBRE.[17] “Center City offers a unique diversity of retailers, services, and restaurants in an easily accessible, dense, walkable, safe setting… in contrast, many malls and shopping centers have grown stale.”

m

Behind these rising rents are a complex constellation of causes that span new urbanism and global capital. On the demand side, cities are booming, and there’s an increased demand for the small-scale, walkable storefronts in which independent businesses thrive. National chains, too, are entering the hunt for space in cities, drawn by rising populations and, having saturated the suburbs, seeking new markets. On the supply side, as older buildings—which were generally designed to have small-scale, ground-level retail space—are getting razed for new development, those new projects often don’t replace them, instead containing commercial space that’s larger-format and designed for a national chain.

For the real estate developers behind these projects, securing a single large ground-floor tenant makes a project easier. A name-brand tenant is a faster ticket to financing for a project, especially within a banking system that’s increasingly national and international in scope. “The way that projects are financed, they go to a safe way of doing development and they have large tenant spaces that make the banks happy that are lending to them,” says Ken Takahashi, in the Seattle Office of Economic Development. This bias toward large spaces in new construction further skews the built environment in favor of bigger companies, and compounds the issue of rising rents. “In a lot of places, the spaces are not the right size for smaller businesses that really only need a fraction of what’s available, and they can’t afford to pay rent on a much larger space,” Takahashi says. Another challenge is that real estate developers and the brokers they hire are often themselves national in scale. They lack knowledge of the local businesses in the market, but already have ongoing relationships with many national brands.

Similar incentives, driven by how buildings are financed, also lead property owners to favor chains. While there is a perception that national chains pay higher rents, that’s not necessarily true. In some cases, it’s local businesses that have to pay higher rents in order to prove themselves, while national chains are given a discount for their perceived stability and credit-worthiness. “A formula retail tenant may not be paying more per square foot, but it adds some credit-worthiness to the balance sheet for the landlord, and it makes your bank happy,” says Rodney Fong, president of Fong Real Estate Company in San Francisco and a member of the San Francisco Planning Commission. Banks and other lenders often provide lower interest rates or better terms if a building owner has signed a national brand. When property owners and investors can get better terms by leasing to a business like a Target, Fong explains, “Target will win every day.”

Structural incentives and geographic biases like these are further distorting the commercial real estate market for locally owned businesses, and making it difficult for them to compete on their own merits. At the same time, property values are soaring, for reasons that include financial speculation and, in the present low interest-rate climate, real estate becoming an increasingly popular place for global investors to park their capital.[18] Combined, these factors are creating rent increases that local businesses can’t absorb. Many of them are forced through the expense and challenge of relocating their business, or closing altogether. In one survey of businesses along Magazine Street in New Orleans, 76 percent of local business owners reported fearing that soaring rents would force them off of the street.[19] A March 2016 report from the city of Boston found that among the city’s primary gaps in its small business ecosystem, “Some gaps, such as a lack of available, affordable real estate, are pervasive and affect most small businesses in the city.”[20]

Continue Reading: to see six broad policy solutions to the problem, and many on-the-ground examples, download the full report.

Notes:

[1] See, for instance: “Cities erupt in youthquake: Millennials swell populations.” Greg Toppo and Paul Overberg, USA Today, May 23, 2013.

[2] “Measuring Up 2015: How U.S. Cities Are Accelerating Progress Toward National Climate Goals.” ICLEI-USA and World Wildlife Fund, Aug. 2015.

[3] “Neighborhood Stores: An Overlooked Strategy for Fighting Global Warming.” Stacy Mitchell, Institute for Local Self-Reliance, Aug. 19, 2009.

[4] “Key Studies: Why Local Matters.” Stacy Mitchell, Institute for Local Self-Reliance, Jan. 8, 2016.

[5] “Older, Smaller, Better: Measuring how the character of buildings and blocks influences urban vitality.” Preservation Green Lab and National Trust for Historic Preservation, May 2014.

[6] “Bronx Leads All Boroughs In Court Evictions of Businesses, Up 30%.” Peter Milosheff, The Bronx Times, Oct. 16, 2015.

[7] “State of the Chains, 2015.” Center for an Urban Future, Dec. 2015.

[8] “Zaro’s Bakery in Parkchester—Iconic Bronx Store—To Close Its Doors.” Welcome2TheBronx, Dec. 22, 2015.

[9] “Landlords Can’t Stop Evicting Latino-Owned Businesses in Washington Heights.” Anita Abedian, The Village Voice, Feb. 9, 2016.

[10] “2016 Independent Business Survey.” Institute for Local Self-Reliance, Feb. 2016.

[11] “Asking Rent Retail for Lease Charleston, SC.” Retail Property Asking Rent — Lease Trends. LoopNet. Accessed April 2016.

[12] “Asking Rent Retail for Lease Cleveland, OH.” Retail Property Asking Rent — Lease Trends. LoopNet. Accessed April 2016.

[13] “Asking Rent Retail for Lease Nashville, TN.” Retail Property Asking Rent — Lease Trends. LoopNet. Accessed April 2016.

[14] “Retail Market Continues to Tighten, Rental Rates Soar.” CBRE Grand Rapids, H1 2015.

[15] “Louisville Retail, H2 2015.” CBRE Research, H2 2015.

[16] “Walk this Way: The Economic Promise of Walkable Places in Metropolitan Washington, D.C.” Christopher B. Leinberger and Mariela Alfonzo, Brookings Institution, May 25, 2012.

[17] “Surging Demand for Urban Retail: Center City Philadelphia.” CBRE, Sept. 2015.

[18] See, for instance: “As Commercial Real-Estate Prices Soar, Fed Weighs Consequences.” Jon Hilsenrath and David Harrison, Wall Street Journal, Dec. 11, 2015; “The Great Wall of Money.” Cushman & Wakefield, March 2016.

[19] “Chain stores, rising rents may make Magazine Street the victim of its success.” Mark Strella and Travis Martin, The Lens NOLA, April 18, 2014.

[20] “City of Boston Small Business Plan.” Mayor Martin J. Walsh, City of Boston, March 2016.