By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When bassist Jeff Halsey first showed up to start his graduate studies at Bowling Green State University he already had some serious playing under his belt.

Through working with the late pianist Claude Black, he performed with saxophonist Jimmy Forrest of “Night Train” fame and Dizzy Gillespie’s drummer J.C. Heard, both of whom had relocated to Michigan.

On the recommendation of Fred Hamilton, the first jazz studies faculty member at BGSU, the bassist took a graduate assistantship in Bowling Green.

When Hamilton left in 1982, Halsey took over the jazz studies program as an interim and a year later was hired as an assistant professor.

Now 38 years later Halsey is retiring. And he plans to keep playing as much as he can.

Of course, the “strange weirdness” of coronavirus pandemic has put a crimp in those plans, he said.

Halsey said he had the busiest few months that he could remember scheduled. But all that’s for naught. His last paying gig was with trombonist Ron Kischuk in Detroit on March 8, and the last concert he played was the following Wednesday with the BGSU faculty and visiting New York pianist Frank Kimbrough.

Since then Halsey has been teaching jazz history and bass lessons using Zoom from home.

For the lectures, he opted to keep some semblance of a routine by delivering them at their appointed time. Still he had students who because of work obligations couldn’t make those times so he recorded and downloaded the lectures. That meant sitting for hours a day as the lectures downloaded.

“I learned a lot,” he said of emergency remote instruction.

This was, he said, a strange way to end his career as a tenured professor. His colleagues did give him a sendoff, but there was not the round of end of year events and performances.

As with other working musicians he found the stay-at-home time a way to reacquaint himself with the fundamentals of his instrument.

Before he spent his practice time working on other people’s music. “Now I have to get in touch with the bass.” Without other people’s music to spur him on, he has to draw that motivation from within himself.

Taking a nod from one of his inspirations, bassist Charlie Haden, Halsey has turned to playing folk songs, as well as working on chord changes.

All that relates to his vision of the bassist’s role in the music. “You’re going to be the foundation and the heartbeat and not showster,” he said. Though, truth be told, Halsey also delivers head-turning solos, as fluid and melodic as any horn player.

Growing up in Grand Rapids, Halsey studied trumpet and classical piano. He’s especially grateful for the piano lessons and has even played a few gigs as a pianist. He refers to his piano playing self as “Melodious Thunk.”

His father was an avocational musician who “worked in a jobbing band on weekends.”

One New Year’s Eve, his bass player called saying he was too sick to make the gig that night. The elder Halsey summoned his 13-year-old son and pulled a bass from the attic. His son didn’t even know the instrument was up there. It only had three strings, but his father instructed him just to keep time.

A bass player was born. From then on Halsey worked with his dad’s band. The older guys helped bring him along, and by the time he was in high school his pals were working the jobs with him.

Halsey father and son would get home from the jobs and talk music, and his future. For a time, those discussions could be heated, Halsey remembers. He wanted to be a jazz musician. His father wanted him to be able to earn a living. Halsey’s mother would have to come in and usher them to bed.

Once the father was convinced his son was serious, he got behind him. Halsey found out that his father had been holding his pay in a bank account, and it was there to help pay for going to college. He earned his bachelor’s degree from Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, which had a strong jazz program.

Halsey met Black, a graduate of Cass High in Detroit, a school that spawned a legend of jazz greats. That opened up the world of music to Halsey. Through him he met Forrest and Heard, and through Heard he met and performed with Gillespie.

It was on a job at Rusty’s Jazz Café in Toledo that Halsey met Hamilton, and that led to BGSU.

The program has now grown with a major and two jazz studies faculty. He realized after a decade that he had to set aside his own preferencs, and be flexible. He decided to open up to the possibilities of what his BGSU colleagues had to offer. “The strength of something is in the diversity,” he said.

He worked with the first faculty ensemble, a trio with vibraphonist Wendell Jones and Hamilton on guitar. As they left BGSU, their replacements, Chris Buzzelli on guitar, Roger Schupp on percussion, and then Russell Schmidt on piano, joined the band.

That was the group that established Wednesday night jazz sessions at a series of venues in downtown.

Halsey remains in the group, which early this year took up residency at Arlyn’s Good Beer, a brew pub started to give the ensemble a permanent home.

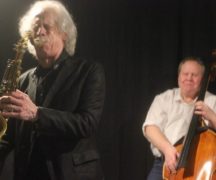

Halsey remains the only holdover in the ensemble that now features David Bixler on alto saxophone, Ariel Kasler on guitar, and Dan Piccolo on drums.

Over the years, a stream of visiting artists have passed through for Jazz Week, the Orchard Guitar Fest, and the Hansen Musical Arts Series. That means the Lab Band I has to learn their music, and the jazz faculty do as well.

Usually with a visiting artist, Halsey said, they have a choice whether to “just play tunes,” those standards that are in every jazz musician’s repertoire, or play the more difficult originals brought in by the visiting artists. They opt for the latter. Guitarist John Scofield, for example, thanked the group for the skill and work they put into learning his charts.

In discussing his retirement, Halsey makes it clear how much he respects and enjoys the work of his colleagues, and appreciates the leadership of the College of Musical Arts by Dean Bill Mathis, who has played trombone on occasion with the faculty jazz ensemble.

At 64 with sore joints, he found “it was just time.”

He’s grown tired of the ever-shifting administrative technology he had to deal with for the mundane aspects of his job.

His wife, Deb, retired from the Toledo Fire Department a few years ago. Their daughter, Elizabeth, is a flute performance major at BGSU. She’s also a talented tap dancer.

Throughout his academic career, Halsey has remained an active freelancer traveling to Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago. For years, he’d worked most of the week as one of the region’s first call jazz bassists. He often performed with Cleveland legend tenor saxophonist Ernie Krivda, and performed with recently deceased jazz master saxophonist Lee Konitz.

“I figured out that teaching and performance go hand in hand,” he said. “I became a better musician because of my teaching and vice versa,” he said.

Even while his peers complained that the work was drying up, he kept busy. Then about 10 years ago, holes opened up in his calendar. He decided that was fine. Schlepping the bass and long, late night drives were taking their toll.

Now everyone’s calendar is a sinkhole. Halsey said he feels bad for friends in places like Detroit, such as Kischuk, who depend on playing and booking music for their livings.

Halsey said he’s going to miss the work in the summer. Playing at Greenfield Village in Michigan were nice relaxing performances, he said.

When the business picks up again, Halsey will be ready to return to the stand.

Given the hiring freeze on campus, there’s even a chance he may be back on campus teaching as an adjunct, and even laying down the groove for sessions at Arlyn’s.